|

|||||

| University of California, Berkeley | |||||

| University Herbarium | |||||

|

|

eFLORA |

|

|

|

|

List of current and former names for California seaweeds |

Voucher-based |

Visual Interactive Keys |

||

|

Index to accepted names and synonyms: | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | |

List of non-native species | NEW TO SEAWEEDS? Click here | ||

|

|

About the ProjectGoals for this websiteHere is a consensus of our knowledge of California seaweeds. I have not attempted to solve taxonomic and nomenclatural problems for the nearly 800 species reported for California. Rather, I want to point out what we know (and what we need to find out) to understand the California seaweeds and their relationships in time and space, much of which can only be understood as historical and cultural, and much of which will change with new information. My goal is to present information on the seaweeds of California, based on the authority of publications from around the world and herbarium specimens in UC and other herbaria. Biogeography provides invaluable clues to species' identities. The ranges of seaweeds included here are based on herbarium collections rather than published endpoints; thus, the basis for this critical information can be checked or tested by looking at the scanned specimen and label information, or by visiting herbaria to ground truth a geographic assertion. Maps derived from UC's database of 62,000 west coast specimens are provided, as are links to other seaweed databases. I hope this approach encourages people who discover range extensions to contribute vouchers to UC or other herbaria. This eFlora will provide species pages for the more or less conspicuous, common species in California, accessed from jargon-free visual keys. Rare, difficult and microscopic species will be treated in a second wave. I hope that the many photos provided here will encourage folks to use their intuition to help them identify and enjoy their legacy on our shores. Since the publication of this landmark book, more than 100 species have been added to California's seaweed flora. More than half of the names have changed since 1976 as a result of new studies. T.C. DeCew and P.C. Silva assembled information about species from Washington, Oregon and northern California, with special reference to phenology (patterns of reproduction) as a function of latitudinal range. Their treatments of green and brown algae are online, while those of red algae are part of the archives at UC. For this website, I have appreciated the wisdom embodied in these treatments and now present their illustrations of red algae for the first time. I draw on my own experience in the field and on what I've learned from the literature and from my many teachers and colleagues, to offer an appreciation of these fabulous marine creatures for everyone — casual observer, coastal ecologist or manager, dedicated professional — whose life or work intersects with California's coast. Kathy Ann Miller How to use this eFloraThere are many resources available to you in the California Seaweeds eFlora. If you want to learn some basics about seaweeds, click on the button New to Seaweeds? for a primer on seaweed biology and ecology.

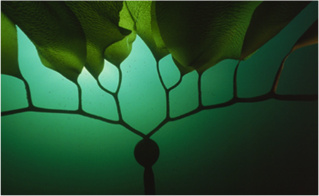

Native species evolved on the coast of North America; Non-native species were introduced to California, by aquaculture, shipping or recreational boating; Cryptogenic species have "hidden origins" - they are broadly distributed and their place of origin is unknown. The photos and images of specimens are high resolution; right click or control click to place them in another tab for close inspection. Click on the species name for the original publication and collector, basionym, and nomenclatural synonyms in the Index Nominum Algarum. Click on Classification for Algaebase.org, whose classification system we follow. Some species pages include phenology tables (reproductive state as a function of latitude) assembled by Tom DeCew for species that occur from San Francisco north. Links to specimen databases are provided. The Setting: Coastal CaliforniaThe magnificent diversity and abundance of seaweed populations along the coast of California reflect the dramatic sweep of this rich coastal environment, embracing rocky shores and reefs, sandy beaches, and offshore islands. Only the floras of Australia and Japan (both with significantly longer coastlines) are more diverse. California straddles the junction of two great biogeographic provinces: the cold temperate Oregonian Province roughly to the north of the northern Channel Islands and Point Conception, and the warmer temperate to subtropical Panamanian Province to the south. The cold California Current, a branch of the Kuroshio Current, runs south along the coast with temperatures from ~9-16° C , shifting offshore near Point Conception, where the coastline veers abruptly east. In the southern California Bight, the warm Davidson Current flows northward in the late summer and autumn, bringing warmer temperatures of ~20° C, but is depressed during spring and early summer months when upwelling brings cold nutrient-rich water to the surface at headlands throughout California and Baja California, Mexico. The iconic kelps of California, those huge, brown, forest-forming seaweeds so unique to our coast, could not survive as far south without these upwelled subsidies. The eight California Channel Islands, in the southern California Bight, are particularly interesting because they are relatively free of coastal development and lie in this mixture of warm and cold currents. History and Herbaria: Our knowledge of California SeaweedsOur scientific knowledge of California seaweeds began with the expeditions of Alessandro Malaspina (Spain) and George Vancouver (Britain) in the 1790s, grew through the long-distance taxonomic efforts of European (e.g., D. Turner, C.A. Agardh, J.G. Agardh, W.H. Harvey, F.J. Ruprecht) and American botanists on the east coast (e.g., A. Gray, W.G. Farlow), and came of age, at the beginning of the 20th century, with the collected works of W.A. Setchell and N.L. Gardner at the University of California at Berkeley (UC). The heart of this story of discovery lies in the herbaria of the world — museums that preserve plant, fungal and algal specimens for botanical research. Herbaria grew out of the "cabinets of curiosities" of earlier centuries, where collectors assembled enduring, beautiful and compelling specimens of natural history — rocks, plants, shells and bones. Today, the world's herbaria house millions of plant specimens, representing the history of our environment and the collective efforts of botanists (and students of botany) to understand and order the plant universe. Particularly valuable are the type specimens. Every time a plant is described, a preserved specimen is designated as the exemplar of that species, and the name is forever associated with that specimen. But because a single specimen cannot encompass the spectrum of expression of that species throughout its life and its geographic range, additional specimens are essential for understanding a species. Herbaria are treasure houses of information, not just about plants, but about people, too — when and where they explored, what they found, and with whom they collaborated. Biogeography and Species RangesBecause the native ranges of many of the "cosmopolitan" species in California are unknown, they are known as "cryptogenic", with hidden origins. Many may be ancient introductions to California. The ships that brought early explorers to our coast (and eager gold miners in the 1840s) were wooden reefs supporting organisms from many ports visited over multi-year voyages, and were probably significant sources of introductions, long before scientists established a baseline for what is indigenous. Organisms from our coast have been introduced to other oceans by the same mechanism. That said, there is evidence that we share genera and species with the western Pacific, especially Japan and Korea, and others with the Atlantic Ocean. At the last glacial maximum, when ice reached as far south as Cape Mendocino, ocean temperature, sea levels and current patterns were very different than they are today, and the Arctic Ocean has opened and closed repeatedly, allowing species to migrate along the boreal "north coast". The geographic distributions of our seaweed species through time are clues to where they evolved, how they have dispersed (naturally or via human intervention) and whether their ranges are currently changing as ocean temperatures, sea levels and current patterns continue to shift. The large-scale biogeographic provinces of marine organisms map to temperature. In California, there is an important "break" between northern and southern species at Point Conception (see county map on the front page of this web site). Some species have broad distributions; kelps, who need cold water to support their large bodies, follow "upwelling" areas (areas where cold, deep water is pushed to the surface by offshore wind patterns) down through southern California and Baja California, Mexico. Many seaweeds tolerate a broad range of temperatures, but may look different (smaller or narrower in warm water) above and below Point Conception. New Frontiers in Seaweed TaxonomySeaweed systematists are critically revisiting nomenclatural history, species identity and geographic ranges. Trends and paradigms in science have determined our interpretations of what we see — and these, like our global climate, shift. We began in an age of "splitting" during which diversity was described in all its expressions. Later, during the exciting explosion of information during the 1960s and 1970s, we entered a time of "lumping", when we realized that individuals could look different due to ecological interactions or life history phase, but were in fact the same species. This trend dominates Marine Algae of California. The well-known propensity of seaweeds to change their form depending on the environment — temperature, wave action, interactions with herbivores — is one of the reasons that it is difficult to distinguish species identity and relationships from form alone. Advanced microscopy has allowed us to look deep into cells and to use minute, internal structures as characters to distinguish algal groups. Growing spores in culture to trace the life history of a species — its mode of reproduction and transition between diploid and haploid phases — has been a powerful method for understanding how a species occupies time and space and has provided clues to relationships. But the revolution in species concepts ignited by using molecular methods to "read" DNA as a set of characters independent of form and environment has opened up a world of new information about species and uncovered "cryptic" species (those that look like others but are genetically distinct) that have never before been recognized. Analyses of DNA sequences from type specimens, housed in the world's herbaria, permit the assignment of names and identities with explicit reference to nomenclatural history — and link contemporary collections to archival specimens. Still, the delineation of species within our most common genera poses daunting challenges to phycologists, who continue to pursue field, culture and molecular studies to determine relationships at every taxonomic level. AcknowledgmentsThe work of great phycologists — W.H. Harvey, C. Agardh, J. Agardh, W.G. Farlow, C.L. Anderson, A.F. Postels, F.J. Ruprecht, W.A. Setchell, N.L. Gardner, H. Kylin, G.M. Smith, E.Y. Dawson, G.J. Hollenberg, P.C. Silva and I.A. Abbott (among so many others) — is the solid bedrock on which our flora rests. In 2008, it was a great joy for me to receive the blessing of Isabella Abbott, who encouraged me to update the seaweed flora of California. Generous financial support from the Packard Foundation Special Opportunity Fund has made this project possible — THANK YOU! I'm deeply grateful to my colleagues, friends and supporters who have joined me in the exploration of the California seaweeds. I appreciate the opportunity to incorporate portions of DeCew's Guide (T.C. DeCew and P.C. Silva), including the unpublished illustrations of red species and some of Silva's taxonomic notes. Richard Moe, David Baxter, and Jason Alexander provided expert IT assistance. Tim Jones designed the fabulous visual keys. Margriet Weatherwax Downing and Ga Hun Boo helped with the assembly of information. I am indebted to photographers who contributed wonderful photos, especially Jessie Alstatt, Dan Richards, Steve Lee, Steve Lonhart, Joe Wible, and Bob Case. Alan Harvey, director of Stanford Press, allowed us to use portions of text from Marine Algae of California (Abbott & Hollenberg 1976), my close and valued companion for the last 40 years. With gratitude, Kathy Ann Miller |

|||

| Copyright © 2024 Regents of the University of California

Citation for this website: Kathy Ann Miller (ed.) 2024. California Seaweeds eFlora, http://ucjeps.berkeley.edu/seaweedflora/ [accessed on April 23, 2024]. We encourage links to these pages, but the content may not be downloaded for reposting, repackaging, redistributing, or sale in any form, without written permission from The University Herbarium. |